Peter Arshinov

History of the Makhnovist Movement (1918–1921)

1923

Chapter 1. Democracy and the Working Masses in the Russian Revolution.

Chapter 2. The October Upheaval in Great Russia and in the Ukraine.

Chapter 3. The Revolutionary Insurrection in the Ukraine. Makhno.

Chapter 4. The Fall of the Hetman. Petliurism. Bolshevism.

Bolshevism. Its Class Character.

Chapter 5. The Makhnovshchina.

Chapter 8. Errors of the Makhnovists. Second Bolshevik Assault on the Insurgent Region.

Chapter 9. Makhnovist Pact With the Soviet Government. Third Bolshevik Assault.

Chapter 10. The Meaning of the National Problem in the Makhnovshchina. The Jewish Question.

Chapter 11. Makhno’s Personality. Biographical Notes on Some Members of the Movement.

Biographical Notes on Some Members of the Movement.

The present work is the first English translation of Peter Arshinov’s Istoriya Makhnovskogo Dvizheniya, originally published in 1923 by the “Gruppa Russkikh Anarkhistov v Germanii” (Group of Russian Anarchists in Germany) in Berlin. It was translated into English by Lorraine and Fredy Perlman.

The English translation follows the Russian original very closely, except in instances when the translators could not find suitable English equivalents for Russian words. The words kulak (wealthy peasant), pomeshchiki (landlords, or gentry), and Cheka (Ch K, the initials of “Extraordinary Commission,” the Bolshevik secret security police) were in general not translated into English, since they refer to very specific Russian phenomena which would be erroneously identified with very different phenomena by available English terms. The Russian territorial division, guberniya, was translated as “government” (and not “province” or “department”) for similar reasons. The Russian word rabochii refers to workers in the narrower sense (industrial workers or factory workers) and was consistently translated as “workers.” However, the Russian word trudyashchiisya is more inclusive and refers to all people who work. In the present translation, the term used for “all those who work” is “working people,” and in passages where the composite term would have made the sentence awkward, “workers” was used (instead of “toilers,” “laborers,” or “working masses,” which have occasionally been used by translators who attempted to maintain the distinction between the two Russian words).

The transliteration of Russian words into English follows generally accepted conventions, though not with absolute consistency. Common first names are given in English. The names of well-known cities and regions are spelled the way they appear on most maps. In one instance, the generally-applied conventions of transliteration were modified for the sake of pronunciation: Gulyai-Pole (pronounced gool-yai pol-ye) is here spelled Gulyai-Polye.

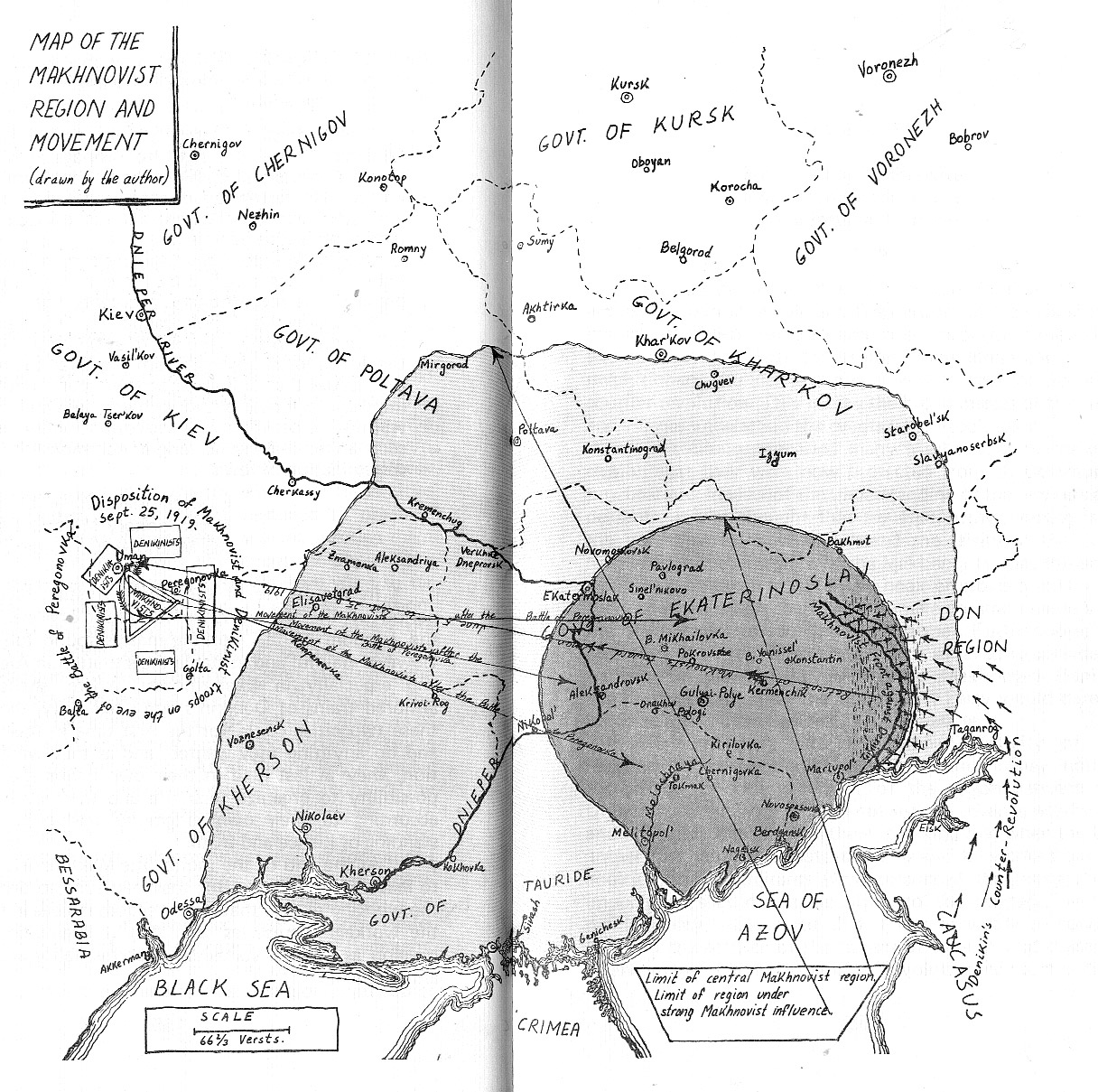

In addition to Voline’s Preface, the map of the insurgent region and the portait of Makhno, all of which appear in the present edition, the original edition also contained an Appendix with a “Protest” by anarchists and syndicalists against Makhno’s arrest and imprisonment in Poland on a false charge. Makhno was released soon after Arshinov’s book appeared, and the “Protest” is not included in the present edition. The Appendix to the present edition contains documents of the Makhnovist movement: eleven proclamations issued by the Makhnovist insurgent army. These proclamations were translated from Russian by Ann Allen.

The people who took part in the publication of the present work are neither publishers who invested capital in order to profit from the sale of a commodity on the book market, nor wage workers who produced a commodity in order to be paid for their time. Every phase of the work — from the translation and editing of the manuscript, to the typesetting and printing of the book — was carried out by individuals who were moved by Arshinov’s account, and who were willing to do the necessary work in order to share this important and virtually unknown book with a larger number of readers.

Voline’s Preface.

As the reader approaches this book he will first of all want to know what kind of work this is: is it a serious and conscientious analysis, or a fantastic and irresponsible fabrication? Can the reader have confidence in the author, at least with respect to the events, the facts and the materials? Is the author sufficiently impartial, or does he distort the truth in order to justify his own ideas and refute those of his opponents?

These are not irrelevant questions.

It is important to examine the documents on the Makhnovist movement with great discretion. The reader will understand this if he considers some of the characteristics of the movement.

On the one hand, the Makhnovshchina[1] — an event of extraordinary breadth, grandeur and importance, which unfolded with exceptional force and played a colossal and extremely complicated role in the destiny of the revolution, undergoing a titanic struggle against all types of reaction, more than once saving the revolution from disaster, extremely rich in vivid and colorful episodes — has attracted widespread interest not only in Russia but also abroad. The Makhnovshchina has given rise to the most diverse feelings in reactionary as well as revolutionary circles: from feelings of fierce hatred and hostility, of astonishment, distrust and suspicion, all the way to profound sympathy and admiration. The monopolization of the revolution by the Communist Party and the “Soviet” power forced the Makhnovshchina, after long hesitation, to embark on a struggle — as bitter as its struggle against the reaction — during which it inflicted on the Party and the central power a series of palpable physical and moral blows. And finally, the personality of Makhno himself — as complex, vivid and powerful as the movement itself — has attracted general attention, arousing simple curiosity or surprise among some, witless indignation or thoughtless fright among others, implacable hatred among still others, and among some, selfless devotion.

Thus it is natural that the Makhnovshchina has tempted more than one “storyteller,” motivated by many considerations other than a genuine knowledge of the events or by the urge to share their knowledge by elucidating the subject and by placing accurate materials at the disposal of future historians. Some of them are driven by political considerations — the need to justify and strengthen their positions, degrading and slandering an inimical movement and its leading figures. Others consider it their duty to attack a phenomenon which frightens and disturbs them. Still others, stimulated by the legend which surrounds the movement and by the lively interest of the “general public” in this sensational theme, are tempted by the prospect of earning some money by writing a novel. Yet others, finally, are simply seized by a journalistic mania.

Thus “material” accumulates which can only create boundless confusion, making it impossible for the reader to sort out the truth.[2]

On the other hand, the Makhnovist movement, in spite of its scope, was forced by a series of circumstances to develop in an atmosphere of seclusion and isolation.

Being a movement composed exclusively of the lowest stratum of the population, being a stranger to all ostentation, fame, domination or glory; originating at the outskirts of Russia, far from the major centers; unfolding in a limited region; isolated not only from the rest of the world but even from other parts of Russia, the movement — its fundamental and profound characteristics — was almost unknown outside of its own region. Developing in conditions of incredibly difficult and tense warfare, surrounded by enemies on all sides, and having almost no friends outside the working class, mercilessly attacked by the governing party and smothered by the bloody and deafening din of it?statist activity, losing at least 90% of its best and most active participants, having neither the time, nor the possibility, nor even a particular need to write down, collect and preserve for posterity its acts, words and thoughts, the movement left very few tangible traces or monuments. Its real development passed by unrecorded. Its documents were neither widely circulated nor preserved. Consequently it has to an enormous extent remained hidden from the view of the outsider or the gaze of the researcher. It is not easy to grasp its essence. Just as thousands of humble individual heroes of revolutionary epochs remain forever unknown, the heroic epic of the Ukrainian workers of the Makhnovist movement has remained almost completely unknown. Until today the treasure of facts and documents of this epic has been completely ignored. And if some of those who took part in the movement, who are thoroughly familiar with it and are also able to report the truth about it, had not by chance remained alive, it might have remained unreported...

This state of affairs puts the serious reader and the historian in a difficult and delicate situation: they must critically untangle and evaluate extremely different and contradictory facts, works and materials, not only without orientation or original data, but also without the slightest indication where such data might be obtained.

This is why it is necessary, from the very beginning, to help the reader separate the wheat from the chaff. This is why it is important for the reader to establish from the start whether or not to consider this work a pure and healthy source. This is why questions about the author and the character of his work are particularly important in this case.

I have taken it upon myself to write a preface for this book to throw light on these questions since, by chance, I am one of the few surviving participants of the Makhnovist movement, and thus possess sufficient knowledge of the movement, of the author, and finally of the conditions in which this book was conceived.

* * *

First I will allow myself a small digression.

I could be asked (and, in fact, am frequently asked) why I don’t write about the Makhnovist movement myself. For many reasons. I can mention several of them.

It is possible to set out on the task of describing and clarifying the events of the Makhnovist movement only on the basis of a thorough and precise knowledge of the facts. The theme requires protracted, intensive and painstaking work. But such work has been impossible for me, for numerous reasons. This is the first reason why I considered it necessary to refrain from dealing with this topic now.

The Makhnovist epic is too serious, lofty and tragic, too heavily drenched with the blood of its participants, too profound, complicated and original, to be described and judged “lightly,” — for example on the basis of the accounts and contradictory interpretations of various individuals. To describe the movement by means of documents is not our project either, since documents by themselves are dead things and can never fully express lived experience. To write on the basis of documents will be the task of future historians, who will have no other materials at their disposal. A contemporary must be much more demanding and severe toward his work and toward himself, since it is precisely on him that history will to a great extent depend. A contemporary must avoid judgments and stories about important events unless he has personally participated in them. Nor is it the task of a contemporary to pounce on the narratives and documents with the aim of “making history,” but rather to set down his personal experience. If this is not done, the writer will risk obscuring or, worse yet, corrupting the very essence, the living soul of the events, misleading, the reader and the historian. Personal experience, to be sure, is not exempted from errors and inaccuracies. But in the present case this is not important. An authentic and vivid picture of the essence of the events will have been drawn — which is what is most important. Comparing this picture with documents and other data will make it easy to locate minor errors. This is why the account of a participant or a witness is particularly important. The more complete and profound the personal experience, the more important and urgent such a work is. If, in addition, the participant himself has documents as well as accounts of other participants, his narrative acquires a relevance of the first order.

I will write about the Makhnovshchina at a later time, in my own way. But I cannot write a complete history of the Makhnovist movement precisely because I do not pretend to have a full, detailed and thorough knowledge of the subject. I took part in the movement for about half a year, from August 1919 to January 1920 — in other words, I hardly observed it in its entirety. I met Makhno for the first time in August 1919. I completely lost sight of the movement and of Makhno in January 1920, when I was arrested; I was in contact with both for only two weeks in November of the same year, at the time of Makhno’s treaty with the Soviet government. After that I again lost sight of the movement. Therefore, even though I saw, experienced and thought a great deal about this movement, my personal knowledge of it is incomplete.

When I am asked why I don’t write about the Makhnovshchina, I answer that there is someone far more capable than I am in this respect.

The person I refer to is the author of the present work.

I knew of his unceasing activity in the movement. In 1919 we worked there together. I also knew that he was carefully collecting material on the movement. I knew that he was arduously writing its complete history. And finally, I knew that the book was finished and that the author was preparing to publish it abroad. And I considered that it was precisely this work that should appear before any other — a complete history of the Makhnovshchina written by a man who, having himself participated in the movement, at the same time possessed a large number of documents.

Many people are still sincerely convinced that Makhno was a “common bandit,” a “pogromshchik,”[3] a leader of a gloomy, war-corrupted, plundering mass of soldier-peasants. Many others consider Makhno an “adventurer,” and believe that he “opened the front” to Denikin, “fraternized” with Petliura, and “allied” with Wrangel... Imitating the Bolsheviks, many people still persist in slandering Makhno, accusing him of being the “leader of a counter-revolutionary kulak movement”; they treat Makhno’s “anarchism” as a naive invention of certain anarchists skillfully applied by him for his own purposes... But Denikin, Petliura and Wrangel are only vivid military episodes: people latch on to them to accumulate a pile of lies. The Makhnovshchina cannot be reduced to the struggle against the counter-revolutionary generals. The essence of the Makhnovist movement, its inner content, its organic characteristics, are almost completely unknown.

This state of things cannot be remedied by short, isolated articles, fragmented observations, partial works. In relation to such an enormous and complex event as the Makhnovshchina, such articles and works offer very little, fail to shed light on the entire picture, and are lost in the sea of printed words, leaving hardly any traces. To deal a decisive blow against all these narratives and to give impetus to serious interest and familiarity with the subject, it is necessary, first of all, to make available a more or less exhaustive work; only then will it be fruitful to turn to the individual questions, the specific events and the details.

The present book is precisely such an exhaustive work. Its author is better suited for this task than anyone else. We only regret the fact that, because of a series of unfortunate circumstances, this work appears after considerable delay.[4]

* * *

It is noteworthy that the first historian of the Makhno-vist movement should be a worker. This fact is not accidental. Throughout its existence, the movement, both ideologically and organizationally, had access only to those forces which could be provided by the mass of workers and peasants. There were, on the whole, no highly educated theorists. During the entire period, the movement was left to itself. And the first historian who sheds light on the movement and gives it a theoretical foundation comes out of its own ranks.

The author, Peter Andreevich Arshinov, son of an Ekaterinoslav factory worker, himself a metalworker by trade, educated himself through strenuous personal effort. In 1904, when he was 17, he joined the revolutionary movement. In 1905, when he was employed as a metalworker in the railway yards of the town of Kizyl-Arvat (in Central Asia), he became a member of the local organization of the Bolshevik Party. He quickly began to play an active role, and became one of the leaders and editors of the local illegal revolutionary workers’ newspaper, Molot (The Hammer). (This newspaper was distributed throughout the railway network of Central Asia and had great importance for the revolutionary movement of the railway workers.) In 1906, pursued by the local police, Arshinov left Central Asia and moved to Ekaterinoslav in the Ukraine. Here he became an anarchist and as such continued his revolutionary work among workers of Ekaterinoslav (especially at the Shoduar factory). He turned to anarchism because of the minimalism of the Bolsheviks which, in Arshinov’s view, did not respond to the real aspirations of the workers and caused, together with the minimalism of the other political parties, the defeat of the 1905–06 revolution. In anarchism Arshinov found, in his own words, a collection of all the libertarian-egalitarian aspirations and hopes of the workers.

In 1906–07, when the Tsarist government covered all of Russia with a network of military tribunals, extensive mass activity became completely impossible. Arshinov, because of personal circumstances as well as his aggressive temperament, carried out several terrorist acts. _

On December 23, 1906, he and several comrades blew up a police station in the workers’ district of Amur, near Ekaterinoslav. (The explosion killed three Cossack officers, as well as police officers and guards of the punitive detachment.) Due to the painstaking preparation of this act, neither Arshinov nor his comrades were discovered by the police.

On March 7, 1907, Arshinov shot Vasilenko, head of the main railroad yard of Aleksandrovsk. Vasilenko’s crime toward the working class consisted of his having turned over to the military tribunal more than 100 working people who were accused of taking part in the armed uprising in Aleksandrovsk in December, 1905; many of them were condemned to death or forced labor because of Vasilenko’s testimony. Before and after this event, Vasilenko was always an active and pitiless oppressor of workers. On his own initiative, but with the agreement and general encouragement of masses of workers, Arshinov bluntly settled accounts with this enemy of the workers, shooting him near the yards while many workers watched. After this act Arshinov was caught by the police, cruelly beaten, and two days later the military tribunal sentenced him to hanging. Suddenly, when the sentence was about to be administered, it was established that Arshinov’s act should by law not be tried by the military tribunal, but by a higher military court. This postponement gave Arshinov the chance to escape. He escaped from the Aleksandrovsk prison on the night of April 22, 1907, during Easter mass, while the prisoners were being led to the prison church. The prison guards assigned to watch the prisoners at the church were surprised by the audacious attack of several comrades; all the guards were killed. All the prisoners had the chance to escape. Fifteen men escaped together with Arshinov.

After this, Arshinov spent about two years abroad, mainly in France. In 1909 he returned to Russia where, for a period of one and a half years, he devoted himself to clandestine anarchist propaganda and organization among workers.

In 1910, while transporting weapons and anarchist literature from Austria to Russia, he was arrested on the frontier by Austrian authorities and jailed in the prison at Tarnopol. After spending about a year in this prison, he was turned over to Russian authorities in Moscow for having committed terroristic acts and was sentenced to 20 years of hard labor by the Court of Assizes in Moscow.

Arshinov served his sentence in the Butyrki prison in Moscow.

It was here, in 1911, that he first met the young Nestor Makhno, who had in 1910 received a life sentence to hard labor for terrorist acts, and who was already familiar with Arshinov’s name and his earlier work in the south. They were close friends during their entire prison term, and both left prison during the first days of the revolution, in March, 1917.

As soon as Makhno was free he left Moscow to take up revolutionary activity in the Ukraine, at his birthplace, Gulyai-Polye. Arshinov remained in Moscow and energetically took part in the work of the Moscow Federation of Anarchist Groups.

When, after the occupation of the Ukraine by the Austro-Germans in the summer of 1918, Makhno spent some time in Moscow in order to acquaint himself and his comrades with the state of affairs, he stayed with Arshinov. Here they got to know each other more intimately, and they ardently discussed the problems of the revolution and of anarchism. When, three or four weeks later, Makhno returned to the Ukraine, he and Arshinov agreed to remain in close contact. Makhno promised not to forget Moscow and to give material assistance to the movement. They spoke of the need to start a journal... Makhno kept his word: he sent money to Moscow (but due to circumstances over which he had no control, Arshinov did not receive it) and wrote to Arshinov several times. In his letters he invited Arshinov to work in the Ukraine; he waited and was irked by the fact that Arshinov did not come.

Sometime later, newspapers began to speak of Makhno as the leader of a powerful partisan detachment.

In April, 1919, at the very beginning of the development of the Makhnovist movement, Arshinov went to Gulyai-Polye and from that time on hardly left the region of the Makhnovshchina until its defeat in 1921. He concerned himself mainly with cultural and educational matters and with organizational work; for some time he directed the cultural and educational section and was editor of the insurgents’ newspaper Put’ k Svobode (The Road to Freedom). He left the region only in the summer of 1920 after a defeat of the movement. During this time he lost a manuscript on the history of the movement which was almost ready for publication. After this absence, it was only with great difficulty that he was able to return to this region which was hemmed in on all sides (by Whites and Reds); he remained there until the beginning of 1921.

At the beginning of 1921, after the third disastrous defeat inflicted on the movement by the Soviet power,[5] Arshinov left the region with a formal assignment; to finish work on the history of the Makhnovist movement. This time he carried the work through to completion in extremely difficult personal circumstances, partly in the Ukraine and partly in Moscow.

* * *

Consequently the author of this book is more competent than anyone else to comment on this subject. He was acquainted with Nestor Makhno long before the events which he describes, and he observed him closely in extremely varied situations during the course of the events. He was also acquainted with all of the remarkable participants of the movement. He was himself an active participant in the events, himself experienced their sublime and tragic development. The profound essence of the Makhnovshchina, its ideological and organizational efforts, aspirations and hopes, were clearer to him than to anyone else. He witnessed its titanic struggle against enemy forces which hemmed it in on all sides. Being a worker himself, he was profoundly imbued with the spirit of the movement: the powerful urge of the working masses, inspired by anarchist ideas, to take their destiny and the construction of a new world into their own hands. As an intelligent and educated worker, he was able to analyze the profound essence of the movement and to contrast it sharply with the ideological essence of other forces, movements and tendencies. Finally, he is thoroughly familiar with all the documents of the movement. He, like no one else, was able to critically examine all accounts and materials, to separate the essential from the inessential, the characteristic from the trivial, the fundamental from the secondary.

All of this allowed him to comprehend and elucidate one of the most original and remarkable episodes of the Russian revolution, in spite of the endless series of unfavorable circumstances and the repeated loss of manuscripts, materials and documents.

* * *

Is it necessary to speak of the individual aspects of this work? It seems to us that the book speaks adequately for itself.

We should emphasize, first of all, that this work was written with exceptional care and exactitude. Not a single doubtful fact was included. On the contrary, a number of interesting and characteristic episodes and details which actually took place were left out by the author with a view to brevity.

Some moments, acts or even entire events were omitted because of the impossibility of verifying them with exact data.

The loss of an entire collection of important documents has certainly been harmful to the work. The last — the fourth — disappearance of the manuscript together with extremely valuable documents crushed the author to such an extent that for a long time he hesitated before setting out again. Only his awareness of the necessity of giving a coherent, even if incomplete, history of the Makhnovshchina drove the author to return to his pen.

It is obvious that later works on the history of the Makhnovist movement will need to be expanded and completed with new data. The movement is so vast, so profound and original, that it cannot yet be fully evaluated. This book is only the first serious contribution toward the analysis of one of the broadest and most instructive revolutionary movements in history.

* * *

Some of the author’s statements of principle can be disputed. But these are not the basic elements of the book and are not developed to their logical conclusions. We might mention the author’s extremely interesting and original evaluation of Bolshevism as a new ruling caste which replaces the bourgeoisie and intentionally aspires to dominate the working masses economically and politically.

* * *

The essence of the Makhnovshchina is brought out in this work more prominently than anywhere else. The very term “Makhnovshchina” acquires, in the work of this author, a broad and almost symbolic meaning. The author uses this term to describe a unique, completely original and independent revolutionary movement of the working class which gradually becomes conscious of itself and steps out on the broad arena of historical activity. The author considers the Makhnovshchina one of the first and most remarkable manifestations of this new movement and, as such, contrasts it to other forces and movements of the revolution. This underlines the fortuitous character of the term “Makhnovshchina.” The movement would have existed without Makhno, since the living forces, the living masses who created and developed the movement, and who brought Makhno forward merely as their talented military leader, would have existed without Makhno. Even if the movement had had another name and its ideological orientation had been different, its essence would have been the same.

The personality and the role of Makhno himself are very sharply drawn in this work.

The relations between the Makhnovist movement and various hostile forces (the counter-revolution, Bolshevism) are masterfully described. The pages devoted to the numerous events of the Makhnovshchina’s heroic struggle against these forces are gripping and overwhelming.

* * *

The extremely interesting question of the mutual relations between the Makhnovshchina and anarchism is not adequately treated by the author. He expresses the salient fact that anarchists on the whole — more precisely, the “summit” anarchists — remained outside the movement; in the author’s words, they “slept through it.” This phenomenon, Arshinov maintains, was caused by the fact that a certain number of anarchists were infected by “Partiinost” (the Party spirit), by the unhealthy urge to lead the masses, their organizations and their movements. This explains the incapacity of these anarchists to understand truly independent mass movements which arise without their knowledge and ask of them only sincere and responsible cultural assistance. This also explains their prejudice and, in essence, their contempt toward such movements. But this statement and explanation are inadequate. The theme should be elaborated and developed. Among anarchists there are three types of views of the Makhnovshchina: decidedly skeptical, neutral, and decidedly favorable. The author, without doubt, belongs to the third group. But his position may be debatable, and he might have to treat the theme more profoundly. It is true that this theme is not related to the essence of the book. Furthermore, the author’s point of view is strongly supported by the facts which he presents throughout the book... Let us hope that this problem will be taken up by the anarchist press, and that a comprehensive treatment of this problem will lead to conclusions useful to the anarchist movement.

* * *

It is certain that all the fables about the banditism, the anti-Semitism, and other somber traits thought to be inherent in the Makhnovist movement, will be discredited by the publication of this book.

If the Makhnovshchina, like every other human project, had its low points, its errors, its deviations, its negative aspects, they were, in the author’s view, so trifling and unimportant in relation to the great positive essence of the movement that it is not worth speaking of them seriously. With the slightest possibility for free and creative development, the movement would have outgrown them without the slightest effort.

* * *

The work shows how lucidly and easily, how straightforwardly the movement transcended various prejudices-national, religious and other. This fact is extremely characteristic: it is yet another example of the level of achievement that the working masses, once aroused by a decisive revolutionary jolt, can reach — and how easily! — if it is actually they themselves who create their revolution, if they have true and complete freedom to search and freedom to act. Their roads are limitless, if only these roads are not intentionally barricaded.

* * *

What seems to us especially noteworthy and important in the present work is:

1) As opposed to many who considered, and continue to consider, the Makhnovshchina only a unique military episode, a foolhardy act of snipers, of partisans with all the faults and all the creative impotence of a military clique (and the relationship of many to the Makhnovist movement was based precisely on such an analysis), the author shows with incontestable data the falsity of such a view. With the greatest precision, the author unfolds before us the picture of a free, creative and organized, though short-lived, movement of the broad working masses, imbued with a profound ideal; a movement which created its own military force in response to its need to defend its revolution and its freedom. A widespread prejudice about the Makhnovshchina is thus destroyed.

It should be noted that, when the author makes a serious critique of the Makhnovshchina, he criticizes precisely a certain negligence in military and strategic affairs. In the chapter on the mistakes of the Makhnovists, he expresses the conviction that if the Makhnovists had in time been able to organize an adequate defense of the outermost frontiers of the region, the whole revolution in the Ukraine as well as in general could have developed very differently. If the author is right, then in this respect the fate of the Makhnovshchina can be compared to that of other revolutionary movements of the past where military errors also played a fatal role. In any case, we call the reader’s attention to this point, which gives rise to very provocative thoughts.

2) The complete independence of the movement is strongly emphasized: an independence which was consciously and energetically defended from all intruding forces.

3) The attitude of Bolshevism and the Soviet Government toward the Makhnovshchina are firmly and precisely established. A shattering blow is dealt to all the inventions and justifications of the Bolsheviks. All their criminal machinations, all their lies, their entire counter-revolutionary essence, are thoroughly exposed. An appropriate inscription to this part of the book would be the words which once escaped from the director of the secret-operations section of the V. Ch. K. [Supreme Cheka], Samsonov (in prison, when I was called for questioning by this “investigator”). When I remarked to him that I considered the behavior of the Bolsheviks toward Makhno, at the time of their treaty with him, treacherous, Samsonov promptly responded: “You consider this treacherous? This simply proves that we are skillful statesmen: when we needed Makhno, we knew how to use him; now that we no longer need him, we know how to liquidate him.”

4) Many sincere revolutionaries consider anarchism an idealistic fantasy and justify Bolshevism as the only possible reality, unavoidable and necessary for the development of the world social revolution, of which it represents a given stage. The dismal aspects of Bolshevism then appear less-important and are historically justified.

The present work deals a death blow to this conception. It vividly establishes two cardinal points: a) anarchist aspirations appeared in the Russian revolution whenever it was a really independent revolution of the working masses themselves, not as a “harmful utopia of visionaries,” but as the real, concrete revolutionary movement of these masses; b) as such it was deliberately, cruelly and basely suppressed by the Bolsheviks.

The facts enumerated in this book clearly show that the “reality” of Bolshevism is, in essence, the same as the reality of Tsarism. These facts concretely and clearly counter-pose this “reality” to the profound truth and reality of anarchism as the only truly revolutionary workers’ ideology, and remove from Bolshevism any trace of historical justification.

5) The book gives anarchists a wealth of materials in the light of which they can review their positions. It brings up several new questions; it provides a series of facts which can help solve a number of earlier questions; finally, it confirms several completely forgotten truths which can usefully be reexamined and reconsidered.

* * *

One last word.

Although this book is written by an anarchist, its interest and significance extend far beyond the limits of one or another circle of readers.

For many people this book will be an unexpected discovery. It will make others aware of the events going on around them. It will throw new light on these events for yet others.

Not only every literate worker or peasant, not only every revolutionary, but also every thinking person who is interested in what goes on around him, should attentively read this book, reflect about the conclusions which flow from it, and be lucidly aware of what it teaches.

Today, when life is fraught with events and the world is replete with struggle; today, when revolution knocks on every door, ready to sweep every mortal into its storm; today, when an immense struggle spreads out in all its amplitude — a struggle not only between labor and capital, between a dying world and a world being born, but also between the advocates of different ways to fight and build; today, when Bolshevism fills the world with its din, demanding blood for its betrayal of the revolution, recruiting adherents by force, treachery and bribery; when Makhno, languishing in a Warsaw prison,[6] could be consoled only by the knowledge that the ideas for which he fought have not died but are spreading and growing — today every book which sheds light on the paths of the revolutionary struggle should be a reference book in every home.

Anarchism is not a privilege of the chosen, but a profound and broad doctrine and conception of the world with which everyone today should be familiar.

The reader need not become an anarchist. But the reader should not experience what happened to an old professor who accidentally attended an anarchist lecture. Moved to tears, after the lecture, he told the listeners gathered around him: “Here am I, a professor, with white hair, and until today I never knew anything about this remarkable and beautiful doctrine... I am ashamed.”

The reader need never become an anarchist; to be an anarchist is not obligatory. But it is necessary to know anarchism.

Voline

May, 1923.

Author’s Preface.

The Makhnovshchina is a colossal event in contemporary Russia. By the breadth and profundity of its ideas, it transcends all the spontaneous working class movements known to us. The factual material about it is enormous. Unfortunately, in the conditions of present day — Communist — reality, one cannot even dream of collecting all the material which could shed light on the movement. This will be the work of the future.

I began to work on the history of the Makhnovist movement four times. All the material relating to the movement was collected for this purpose. But four times the work was destroyed when it was half finished. Twice it was lost at the front during a battle, and two other times in peaceful lodgings during searches. Exceptionally precious documentation was lost in Khar’kov in January, 1921. This material contained everything one could have wanted to know about the front, the Makhnovist camp and the personal archives of Makhno: it included Makhno’s memoirs containing a great quantity of facts, most of the publications and documents of the movement, a complete collection of the newspaper Put’ k Svobode, detailed biographical notes on the most devoted participants of the movement. It is absolutely impossible to reconstruct the lost documentation even partially. Thus I had to complete the present work lacking many of the necessary materials. Furthermore, the work was at first carried out between battles, and later in the extremely unfavorable repressive conditions of contemporary Russia, where I wrote the same way as convicts in Tsarist prisons wrote each other, namely by hiding in any corner or behind a table, with constant fear of being discovered by the guard.

For these reasons it is natural that the work should appear hasty and should contain several gaps. However, the current state of affairs demands that a work on the history of the movement should be issued, even if it is incomplete. Consequently this work is not definitive. It is only a beginning and should be continued and further elaborated. But for this purpose it will be necessary to collect all the materials that relate to the movement. All comrades who possess any of this material are urged to pass them on to the author.

* * *

In this preface I would like to say a few words to comrades-workers in other countries. Many among them, arriving in Russia to attend some congress, see contemporary Russia in an official framework. They visit the factories of Petrograd, Moscow and other cities and learn about their conditions on the basis of data furnished by the governmental party or political groups related to it. Such an acquaintance with Russian reality has no value. The guests are everywhere shown a life which is very far from reality. For example. In 1912 or 1913 a scientist from Amsterdam (Israel Van Kan, if I’m not mistaken) came to Russia to investigate Russian jails and prisons. The Tsarist government gave him the opportunity to observe prisons in Petrograd, Moscow and other cities. The professor strolled from cell to cell, informing himself about the situation of the convicts, and talking with them. In spite of the fact that he established illegal relations with some political prisoners (Minor and others), in the Russian prisons he saw no more than what the prison administration wanted to show him; that which was specific to Russian prisons escaped him. Foreign comrades and workers who come to Russia hoping to become familiar with Russian life in a short time with the help of data furnished by the governing party or by rival politicians, find themselves in the same situation as Israel Van Kan. They unavoidably commit gross errors.

In order to experience Russian reality, it is indispensable to go to the country as a simple agricultural worker, or to a factory as a laborer, to receive the economic and political payok (ration) granted to the people by the Communist government, to demand the sacred rights of workers and struggle to obtain them when they are not granted, and to struggle in a revolutionary manner, since revolution is the supreme right of workers. Only then will the actual and not the staged Russian reality be visible to such a daring observer. And then he will not be surprised by the history recorded in this book. With horror and shock he will see that in Russia today, as everywhere else, the great truth of the working class is persecuted and tortured and the heroism of the Makhnovist movement which defended this truth will be clear to him.

It seems to me that every thinking proletarian concerned with the fate of his class will agree that only in this way can one become familiar with Russian — or any other-life. Everything that has until today been the common practice of foreign delegations who came to study Russian life has consisted of trifles, illusions, picnics abroad, a pure waste of time.

Arshinov

Moscow

April, 1921.

P.S. I consider it a pleasant comradely obligation on my own part and on the part of the other participants of the movement, to express my gratitude to all organizations and comrades who helped or tried to help in the work of publishing this book: the Federation of Anarcho-Communist Groups of North America, as well as Italian and Bulgarian comrades.

May, 1923.

Chapter 1. Democracy and the Working Masses in the Russian Revolution.

There has not been one revolution in the world’s history which was carried out by the working people in their own interests — by urban workers and poor peasants who do not exploit the work of others. Although the main force of all great revolutions consisted of workers and peasants, who made innumerable sacrifices for their success, the leaders, ideologists and organizers of the forms and goals of the revolution were invariably neither workers nor peasants, but elements foreign to the workers and peasants, generally intermediaries who hesitated between the ruling class of the dying epoch and the proletariat of the cities and fields.

This element was always born and grew out of the soil of the disintegrating old regime, the old State system, and was nourished by the existence of a movement for freedom among the enslaved masses. Because of their class characteristics and their aspiration to State power, they take a revolutionary position in relation to the dying political regime and readily become leaders of enslaved workers, leaders of mass revolutionary movements. But, while organizing the revolution and leading it under the banner of the vital interests of workers and peasants, this element always pursues its own group or caste interest, and aspires to make use of the revolution with the aim of establishing its own dominant position in the country. This is what happened in the English revolution. This is what happened in the great French revolution. This is what happened in the French and German revolutions of 1848. This is what happened in a whole series of other revolutions where the proletariat of the cities and the countryside fought for freedom, and spilled their blood profusely — and the fruits of their efforts and sacrifices were divided up by the leaders, politicians with varied labels, operating behind the backs of the people to exploit the tasks and goals of the revolution in the interest of their groups.

In the great French revolution, the workers made colossal efforts and sacrifices for its triumph. But the politicians of this revolution: were they the sons of the proletariat and did they fight for its aspirations — equality and freedom? In no way. Danton, Robespierre, Camille Desmoulins and a whole series of other “high priests” of the revolution were representatives of the liberal bourgeoisie of the time. They struggled for a specific bourgeois type of social relations, and in fact had nothing in common with the revolutionary ideals of equality and freedom of the French popular masses of the 18th century. Yet they were, and still are, generally considered the leaders of the great revolution. In the 1848 revolution the French working class, which had given up to the revolution three months of heroic efforts, misery, privation and sacrifice — did they obtain the “social republic” which had been promised by the managers of the revolution? The working class harvested from them only slavery and mass killings; 50 thousand workers were shot in Paris, when they attempted to rise up against those treacherous leaders.

The workers and peasants of all past revolutions succeeded only in sketching their fundamental aspirations, only in defining their course, which was generally perverted and then liquidated by the cleverer, more cunning and better educated “leaders” of the revolution. The most the workers got from these revolutions was an insignificant bone, in the form of the right to vote, to gather, to print — in the form of the right to choose their rulers. And even this bone was given to them for a short time, the time needed by the new regime to consolidate itself. After this the life of the masses returned to its former course of submission, exploitation and fraud.

It is only in mass movements from below, like the revolt of Razin, or like the revolutionary peasant and worker insurrections of our time, that the people become the masters of the movement, giving it its form and content. But these movements, which are usually greeted by the abuse and the curses of all “thinking” people, have never yet triumphed, and they differ sharply, in terms of their content as well as their form, from revolutions led by political groups and parties.

Our Russian revolution is, without a doubt, a political revolution which uses the forces of the people to serve interests foreign to the people. The fundamental fact of this revolution, with a background of enormous sacrifices, sufferings and revolutionary efforts of workers and peasants, is the seizure of political power by an intermediary group, the so-called socialist revolutionary intelligentsia, the Social Democrats.

A great deal has been written about the Russian as well as the international intelligentsia. They are generally praised, and called the carriers of the highest human ideals, champions of eternal truth. They are rarely abused. But all that has been written about them, the good and the bad, has one essential shortcoming: namely, they are defined by themselves, praised by themselves and abused by themselves. To the independent mind of workers or peasants this is completely unconvincing and can have no weight in the relations between the intellectuals and the people. In these relations the people are concerned only with facts. The real, indisputable fact of life of the socialist intelligentsia is the fact that they have always enjoyed a privileged social position. Living in privilege, the intelligentsia became privileged not only socially but also psychologically. All their spiritual aspirations, everything they call their “social ideals,” inevitably carries within itself the spirit of caste privilege. We come across it thoughout the entire social development of the intelligentsia. If we take the era of the Decembrists as the beginning of the revolutionary movement of the intelligentsia, and pass consecutively through all the stages of this movement — the “Narodnichestvo,” the “Narodovol’chestvo,” Marxism and socialism in general with all their ramifications — we find this spirit of caste privilege clearly expressed throughout.

No matter how lofty a social ideal may be externally, as soon as it carries within itself privileges for which the people will have to pay with their work and their rights, it is no longer the complete truth. A social ideal which does not offer the people the whole truth is a lie for them. It is precisely such a lie that the ideology of the socialist intellectuals, and the intellectuals themselves, represent to the people. This fact determines everything about the relations between the people and the intelligentsia. The people will never forget and forgive the fact that, speculating on their forced labor and lack of rights, a certain social group created social privileges for itself and tried to carry them into the new society.

The people — that’s one thing; democracy and its socialist ideology — that’s something else, which comes to the people prudently and cunningly. Certainly isolated heroic individuals, like Sofya Perovskaya, stood above the vile privileges inherent in socialism, but only because they did not understand reality in terms of a democratic-class doctrine, but psychologically or ethically. These are the flowers of life, the beauty of the human race. Inspired by the passion for truth, they lived entirely to serve the people and by their beautiful example exposed the false character of the socialist ideology. The people will never forget them and will eternally carry a great love for them in their hearts.

The vague political aspirations of the Russian intelligentsia in 1825 took shape during the course of half a century in a perfected socialistic Statist system, and this intelligentsia itself, in a well-defined social-economic group: the socialist democracy. The relations between this intelligentsia and the people were definitively established: the people moved toward civic and economic self-determination; the democrats aspired to power over them. The connection between them could be maintained only by means of cunning, trickery and violence, but in no way as the natural result of a community of interests. They are hostile toward each other.

The doctrine of the State itself, the idea of managing the masses by force, was always an attribute of individuals who lacked the sentiment of equality and in whom the instinct of egoism was dominant; individuals for whom the human masses are a raw material lacking will, initiative and intelligence, incapable of directing themselves.

This idea was always held by dominant privileged groups who stood outside the working population — the aristocracy, military castes, nobility, clergy, industrial and commercial bourgeoisie, etc.

It is not by chance that contemporary socialism shows itself to be the zealous servant of this idea: it is the ideology of the new ruling caste. If we attentively observe the carriers and apostles of state socialism, we will see that every one of them is full of centralist urges, that every one sees himself, above all, as a directing and commanding center around which the masses gravitate. This psychological trait of state socialism and its carriers is a direct outgrowth of the psychology of former groups of rulers which are extinct or in the process of dying.

The second fundamental fact of our revolution is that the workers and the peasant laborers remained within the earlier situation of “working classes” — producers managed by authority from above.

All the present day so-called socialist construction carried out in Russia, the entire State apparatus and management of the country, the creation of new social-political relations — all this is largely nothing other than the construction of a new class domination over the producers, the establishment of a new socialist power over them. The plan for this construction and this domination was elaborated and prepared during several decades by the leaders of the socialist democracy and was known before the Russian revolution by the name of collectivism. Today it calls itself the soviet system.

This system makes its first historical appearance on the soil of the revolutionary movement of Russian workers and peasants. This is the first attempt of socialist democracy to establish its statist domination in a country by the force of a revolution. As a first attempt, undertaken at that by only one part of the democracy — by the most active, most enterprising and most revolutionary part, its communist left wing — it surprised the broad masses of democrats, and its brutal forms at first split the democracy itself into several rival groups. Some of these groups (Mensheviks, Socialist-Revolutionaries, etc.) considered it premature and risky to introduce communism into Russia at the present time. They retained the hope of achieving State domination in the country by the so-called legal and parliamentary route: by winning the majority of seats in parliament by means of votes from workers and peasants. This was the basis of their disagreement with their left-wing colleagues, the Communists. This disagreement is temporary, accidental and not serious. It is provoked by a misunderstanding on the part of the broader and more timid section of democrats, who failed to understand the meaning of the political upheaval carried out by the Bolsheviks. As soon as this group sees that the communist system does not contain anything that threatens them, but on the contrary opens up to them superb posts in the new State, all the disagreements between the rival factions of the democracy will disappear, and the entire democracy will carry on under the guidance of the unified Communist Party.

And already today we observe a certain “enlightenment” of the democracy in this direction. A whole series of groups and parties, in Russia and abroad, are rallying to the “soviet platform.” Enormous political parties from different countries, until recently animators of the Second International, who fought Bolshevism from that standpoint, are today preparing to join the Communist International and present themselves to the working class with the Communist flag, with “Dictatorship of the Proletariat” on their lips.

But, as in earlier great revolutions in which workers and peasants fought, our revolution was also accompanied by a series of original and independent struggles of working people for freedom and equality, profound currents which marked the revolution. One of these currents, the most powerful and the most vivid, is the Makhnovshchina. For a period of three years the Makhnovshchina heroically cleared a path in the revolution by which the working people of Russia could realize their age-old aspirations — freedom and independence. In spite of the savage policy of the Communist government to smother this current, to distort and befoul it, it continued to grow, live and develop, struggling on several fronts in the civil war, frequently dealing serious blows to its enemies, arousing and supporting the revolutionary expectations of the workers and peasants of Great Russia, Siberia and the Caucasus. The continued development of the Makhnovshchina is explained by the fact that many of the Russian workers and peasants were to some extent familiar with the histories of revolutions of other peoples as well as the revolutionary movements of their ancestors, and were able to lean on this experience. In addition, workers came out of the ranks who were able to find, formulate, and attract the attention of the masses, to the most fundamental and basic aspects of their revolutionary movement, to contrast these aspects with the political goals of the democracy, and to defend the workers’ aspirations with dignity, perseverance and talent.

Before going on to the history of the Makhnovist movement, it is necessary to note that, when the Russian revolution is called the “October Revolution,” two distinct phenomena are confused: the slogans under which the masses carried out the revolution, and its results.

The slogans of the October 1917 mass movement were: “The Factories to the Workers! The Land to the Peasants!” The entire social and revolutionary program of the masses is communicated by this brief but profoundly significant slogan: the destruction of capitalism, wage labor, enslavement to the State, and the organization of a new life based on the self-direction of the producers. But in reality this October program was not realized in any way. Capitalism has not been destroyed but reformed. Wage labor and the exploitation of the producers remains in force. And the new State apparatus oppresses the workers no less than the State apparatus of landowners and private capitalists. Thus the Russian revolution can be called the “October revolution” only in a specific and narrow sense: as a realization of the goals and tasks of the Communist Party.

The October upheaval, as well as the one of February-March 1917, was only a stage in the general advance of the Russian revolution. The revolutionary forces of the October movement were used by the Communist Party for its own plans and goals. But this act does not represent our entire revolution. The general course of the revolution includes a whole series of other currents which do not stop in October but go further, toward the implementation of the historic tasks of the workers and peasants: the egalitarian, stateless community of workers. The currently protracted and already hardened October must, without a doubt, give way to the next popular stage of the revolution. If this does not happen, the Russian revolution, like all its predecessors, will have been nothing but a change of government.

Chapter 2. The October Upheaval in Great Russia and in the Ukraine.

To clarify the development of the Russian revolution, it is necessary to examine the propaganda and the development of revolutionary ideas among the workers and the peasants throughout the period from 1900 to 1917, and the significance of the October upheaval in Great Russia and in the Ukraine.

Beginning with the years 1900–1905, revolutionary propaganda among workers and peasants was carried out by spokesmen of two basic doctrines: state socialism and anarchism. The state socialist propaganda was carried out by a number of wonderfully organized democratic parties: Bolsheviks, Mensheviks, Socialist-Revolutionaries and a number of related currents. Anarchism was put forward by a few numerically small groups who did not have a sufficiently clear understanding of their tasks in the revolution. The field of propaganda and political education was almost completely occupied by the democracy which educated the masses in the spirit of its political program and ideals. The establishment of a democratic republic was its basic goal; political revolution, its means to realize this goal.

Anarchism, on the contrary, rejected democracy as one form of statism, and also rejected political revolution as a method of action. Anarchism considered the basic task of workers and peasants to be social revolution, and it is for this that it called the masses. This was the sole doctrine which called for the complete destruction of capitalism in the name of a free, stateless society of working people. But, having only a small number of militants and at the same time lacking a concrete program for the immediate future, anarchism could not spread widely and establish roots among the masses as their specific social and political theory. Nevertheless, because anarchism dealt with the most important aspects of the life of the enslaved masses, because it was never hypocritical toward them, and taught them to struggle directly for their own cause and to die for it — it created a gallery of fighters and martyrs for the social revolution at the very heart of the working class. Anarchist ideas held out through the long ordeal of Tsarist reaction and remained in the hearts of individual workers of cities and countryside as their social and political ideal.

Socialism, being a natural offspring of democracy, always had at its disposal enormous intellectual forces. Students, professors, doctors, lawyers, journalists, etc., were either patented Marxists or to a great extent sympathized with Marxism. Thanks to its extensive forces experienced in politics, socialism always succeeded in attracting a significant number of workers, even though it called them to a struggle for the incomprehensible and suspect ideals of the democracy.

In spite of this, at the time of the 1917 revolution, class interests and instincts led the workers and peasants toward their own direct goals: the appropriation of land and factories.

When this orientation appeared among the masses — and it appeared long before the 1917 revolution — one section of the Marxists, namely their left wing, the Bolsheviks, quickly abandoned their overtly bourgeois-democratic positions, proclaimed slogans which were adapted to the needs of the working class, and in the days of the revolution marched with the rebellious mass, seeking to make themselves masters of the mass movement. They succeeded in this thanks to the extensive intellectual forces in the ranks of Bolshevism as well as the socialist slogans with which they seduced the masses.

We have already mentioned above that the October upheaval was carried out under two powerful slogans: “Factories to the Workers; Land to the Peasants!” The working people gave these slogans a plain meaning, without reservations; i.e., the revolution would place the entire industrial economy directly under the control of the workers, the land and agriculture under that of the peasants. The spirit of justice and self-activity contained in these slogans inspired the masses to such an extent that a significant and very active part of them was ready the day after the revolution to start organizing life on the basis of these slogans. In numerous cities the trade unions and factory committees took over the management of the factories and their goods, getting rid of the proprietors, and themselves determined prices, etc. But all these attempts met the iron resistance of the Communist Party which had already become the State.

The Communist Party, which marched shoulder to shoulder with the revolutionary masses and took up their extremist, frequently anarchist, slogans, abruptly transformed its activity as soon as the coalition government was discarded and the Party came to power. The revolution as a mass movement of working people with the slogans of October, was from that point on finished for the party. The basic enemy of the working class, the industrial and agricultural bourgeoisie, was defeated. The period of destruction, of struggle against the capitalist regime, was over; what began was the period of communist construction, the period of proletarian building. From this point on, the revolution could only be carried out by the organs of the State. The continuation of the earlier condition of the country, when the workers were masters of the streets, factories and workshops, when the peasants, not seeing the new power, tried to arrange their lives independently, could have dangerous consequences and could disorganize the Party’s role in the State apparatus. All this had to be stopped by all possible means, up to and including State violence.

Such was the about-face in the activity of the Communist Party as soon as it seized power.

From this moment on, the Party obstinately reacted against all socialist activity on the part of the masses of workers and peasants. Obviously, this about-face of the revolution and this bureaucratic plan for its further development was a cowardly and impudent step on the part of a party that owed its position only to the working people. This was pure imposture and usurpation. But the logic of the position taken by the Communist Party in the revolution was such that it could not have acted otherwise. Any other political party seeking dictatorship and supremacy over the country from the revolution would have acted the same way. Before October it was the right wing of the democracy which sought to command the revolution — Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries. Their difference with the Bolsheviks was that they were not able to organize their power and catch the masses in their nets.

* * *

Let us now examine how the dictatorship of the Communist Party and its ban on the further development of the revolution outside the organs of the State were received by the working people of Great Russia and the Ukraine. For the workers of Great Russia and the Ukraine, the revolution was the same, but the Bolshevik statist domination of the revolution was not received the same way: in the Ukraine it met more resistance than in Great Russia. Let us begin with Great Russia.

Before and during the revolution, the Communist Party carried on enormous activity among the workers of the cities of Great Russia. During the Tsarist period it tried, being the left wing of social-democracy, to organize them for the struggle for a democratic republic, recruiting a reliable and solid army from among them to struggle for its ideals.

After the overthrow of Tsarism in February-March 1917, a tense period began, when the workers and peasants could not afford to lose any time. The working people saw the provisional government as their avowed enemy. Thus they did not wait to set out to realize their rights by revolutionary means: first of all their right to the eight-hour day, then their rights to the instruments of production and consumption as well as the land. In all this the Communist Party presented itself to them as a superbly organized ally. It is true that through this alliance the Party followed its own aims, but the masses did not know this, and only saw the fact that the Communist Party struggled with them against the capitalist regime. This party directed all the power of its organizations, all its political and organizational experience, its best militants, into the heart of the working class and into the army. The party used all its forces to assemble the masses around its slogans, playing demagogically with the burning questions of the oppressed laborers, snatching the slogans of the peasants about the land, of the workers about voluntary labor, and pushed the working people toward a decisive clash with the coalition government. Day after day, the Communist Party was in the ranks of the working class, carrying on with the workers an untiring struggle against the bourgeoisie, a struggle which it continued until the days of October. Thus it is natural that the workers of Great Russia were accustomed to see in the Party their energetic comrades-in-arms in the revolutionary struggle. This circumstance, as well as the fact that the Russian working class had almost no revolutionary organizations of its own — it was scattered, from an organizational standpoint — allowed the party to easily take the management of affairs into its hands. And when the coalition government was overturned by the working class of Petrograd and Moscow, power simply passed to the Bolsheviks as the leaders of the upheaval.

After this the Communist Party directed all of its energy toward the organization of a firm power and to the liquidation of mass movements of workers and peasants which continued, in various parts of the country, to try to achieve the basic goals of the revolution by means of direct action. The party succeeded in this task without great difficulty due to the enormous influence which it had acquired in the period which preceded October. It is true that immediately after its seizure of power, the Communist Party was obliged, more than once, to stifle the first steps of workers’ organizations trying to start production in their enterprises on the basis of workers’ equality. It is true that numerous villages were pillaged and thousands of peasants were assassinated by the Communist power for their disobedience and their attempts to do without state power. It is true that in Moscow and in several other cities, in order to liquidate anarchist organizations in April 1918, and later, organizations of the left Socialist-Revolutionaries, the Communist Party was forced to use machine guns and cannons, thus provoking a civil war on the left. But in general, due to a certain confidence of Great Russian workers in Bolshevism after October, a confidence which was short-lived, the Bolsheviks succeeded easily and quickly in taking the masses in hand and in stopping the further development of the workers’ and peasants’ revolution, replacing it with the governmental decrees of the Party. That ended the revolution in Great Russia.

The period before and during October was very different in the Ukraine. Here the Communist Party did not have a tenth of the organized party forces which it possessed in Great Russia. Here its influence on the peasants and workers had always been insignificant. Here the October upheaval took place much later, not until November, December, and January of the following year. Up to this point the Ukraine had been ruled by the local national bourgeoisie — the Petliurovtsi (followers of Petliura). In their relations to the Ukraine, the Bolsheviks did not act in a revolutionary manner, but mainly in a military manner. In Great Russia the passage of power to the Soviets meant its passage to the Communist Party. However in the Ukraine, thanks to the powerlessness and unpopularity of the Communist Party, the passage of power to the Soviets meant something completely different. The Soviets were meetings of delegated workers without any real power to subordinate the masses. The workers in the factories and the peasants in the villages felt themselves to be the real force. But this force was scattered, disorganized, and constantly in danger of falling under the dictatorship of a well-knit party.

During the entire revolutionary struggle, the working class and the peasants of the Ukraine were not accustomed to being surrounded by an ever-present and inflexible tutor like the Communist Party in Great Russia. As a result, the working population experienced a much greater degree of freedom, which inevitably manifested itself during the days of mass revolutionary activity.

Another, still more important aspect of the life of (indigenous) Ukrainian peasants and workers were the traditions of the Vol’nitsa which were preserved from ancient times. Whatever efforts the Tsars made, from Catherine II on, to wipe out all traces of the Vol’nitsa from the minds of the Ukrainian people, this heritage from the heroic epoch of Zaporozh’e Cossacks of the 14th to the 16th century is nevertheless preserved to the present day, and Ukrainian peasants have retained a particular love for independence. Among present-day Ukrainian peasants this takes the form of stubborn resistance to all powers which try to subjugate them.

The revolutionary movement in the Ukraine was thus accompanied by two conditions which did not exist in Great Russia, and which greatly influenced the character of the Ukrainian revolution: the absence of a powerful and organized political party, and the spirit of the Vol’nitsa, a living heritage of the Ukrainian worker, And in fact, when the revolution in Great Russia fell under the domination of the State without much resistance, this domination met great resistance in the Ukraine. The Soviet apparatus installed itself mechanically, and mainly by armed force. At the same time an autonomous mass movement consisting mainly of peasants continued to develop. It had appeared already under the government of the Democratic Republic of Petliura and progressed slowly, still seeking its path. Furthermore, the roots of this movement lay at the very basis of the Russian revolution. It was noteworthy already from the first days of the February upheaval. It was a movement of the lowest strata of the working people, who sought to destroy the economic slave system and create a new system, based on the socialization of means and instruments of labor and the cultivation of the land by the workers themselves.

We have already mentioned that, in the name of these principles, workers got rid of the owners of factories and transferred the management of production to their class organs: trade unions, factory committees or workers’ commissions specially created for this purpose. The peasants took over the land of the pomeshchiks (gentry) and of the kulaks (wealthy peasants) and reserved the produce strictly for the workers themselves, thus sketching a new type of agrarian economy.

This practice of direct revolutionary action by the workers and peasants developed in the Ukraine almost unobstructed during the whole first year of the revolution and created a healthy and clear line of revolutionary conduct for the masses.

And every time one or another political group, having taken power, tried to break the workers’ line of revolutionary conduct, the workers launched a revolutionary opposition and struggled in various ways against these attempts.

Thus the revolutionary movement of the working people toward social independence, which had begun in the first days of the revolution, did not weaken no matter what power was established in the Ukraine. It was not even extinguished by the Bolsheviks who, after the October upheaval, tried to introduce their autocratic state system into the country.

What was characteristic about this movement?

Its desire to attain the real goals of the working class in the revolution; its will to win labor’s independence; its defiance of all non-laboring social groups.

Despite all the sophisms of the Communist Party seeking to prove that the Party was the brain of the working class, and that its power was that of the workers and peasants — every worker and peasant who had retained his class spirit or instinct was aware that in fact the Party was driving the workers of the cities and the countryside away from their own revolutionary tasks, that the Party had them under its control, and that the very existence of a statist organization was a usurpation of their right to independence and to any form of self-management.

The aspiration to full self-direction became the basis of the movement born in the depths of the masses. In all kinds of ways their thoughts were constantly rooted in this idea. The statist activity of the Communist Party pitilessly stifled these aspirations. But it was precisely this action of the presumptuous party, intolerant of any objection, that enlightened the workers and drove them to resist.

In the beginning, the movement confined itself to ignoring the new power and performing spontaneous acts in which the peasants took possession of the land and goods of the landlords. They found their own ways and means. The unexpected occupation of the Ukraine by the Austro-Germans placed the workers in a completely new situation and precipitated the development of their movement.

Chapter 3. The Revolutionary Insurrection in the Ukraine. Makhno.

The Brest-Litovsk treaty concluded by the Bolsheviks with the Imperial German government opened the doors of the Ukraine to the Austro-Germans. They entered as masters. They did not confine themselves to military action, but became involved in the economic and political life of the country. Their purpose was to appropriate its products. To accomplish this easily and completely they reestablished the power of the nobles and the landed gentry, who had been overthrown by the people, and installed the autocratic government of the Hetman Skoropadsky. Their troops were systematically misled by their officers about the Russian revolution. The situation in Russia and the Ukraine was represented to them as an orgy of blind, savage forces, destroying order in the country and terrorizing the honest working people. This way they provoked in the soldiers a hostility towards the rebel peasants and workers, thus creating the basis for the absolutely heartless and plundering entry of the Austro-German armies into the revolutionary country.

The economic pillage of the Ukraine by the Austro-Germans, with the connivance and help of the Skoropadsky government, was colossal and horrifying. They carried off everything — wheat, livestock, poultry, eggs, raw materials, etc. — all in such quantities that the means of transportation were not sufficient. As it was brought to the immense depots which were given over to the loot, the Austrians and the Germans hastened to take away as much as possible, loading one train after another. Hundreds, even thousands of trains, carried everything off. When the peasants resisted this pillage and tried to retain the fruits of their labor, floggings, reprisals and shootings resulted.

The occupation of the Ukraine by the Austro-Germans constitutes one of the most tragic pages in the history of its revolution. In addition to the violence of the invaders and their cynical military brigandage, the occupation was accompanied by a fierce reaction on the part of the landed gentry. The Hetman’s regime meant the annihilation of all the revolutionary conquests of the workers, a complete return to the past. It was therefore natural that this new condition strongly accelerated the march of the movements previously begun, under Petliura and the Bolsheviks. Everywhere, primarily in the villages, insurrectionary acts began against the landowners and the Austro-Germans. It was thus that the new revolutionary movement of the Ukrainian peasants began, a movement which was later given the name of the Revolutionary Insurrection. The origin of this revolutionary insurrection is often seen as merely the result of the Austro-German occupation and the regime of the Hetman. This explanation is insufficient and therefore not true. The insurrection had its roots in the depths of the Russian revolution and was an attempt by the workers to lead the revolution to its natural conclusion: the true and complete emancipation and supremacy of labor. The Austro-German invasion and the pomeshchiks’ (landowners’) reaction only accelerated the process.