There are three main areas of playing the game of Diplomacy: Tactics

or what the pieces are able to do, Strategy what the relation between

the countries and alliances are and finally the mind set and

interactions with the players as individuals. Before we get into

grandiose manipulation of this knowledge to the great glory of the one

closest to your own heart, we have to know how to read the basics of

these Pieces/Position/Players.

Reading the Pieces

One of the oldest lines

in Diplomacy is “The pieces never lie” -- when you review the pieces on

the board and look at the individual or combined immediate moves, they

should tell you a story of possibilities. NOTE it is not probabilities.

When reading the pieces, ignore the people, the alliances, and

concentrate on what can happen. Allow yourself to discard a few aspects

but do not put blinders on about the capabilities of the pieces.

Players, unfortunately, have a tendency to ignore some of these more

common move combinations: Convoys, most typically:

- Army Kiel to Livonia convoyed by Fleet Baltic

- Army Spain to Tuscany convoyed by Fleet Gulf of Lyon

- Army Greece to Apulia convoyed by Adriatic or Ionian

- Switch of positions using fleets such as Army Bulgaria-Rumania convoyed by Fleet Black Sea

- Any combination of other players making a convoy. For example:

Italy using Fleets Ionian with Turkish Fleet Aegean to swing an army

from Smyna to Albania

Basic Rule of Support: You cannot cut support for an attack on

yourself. This is often over looked when there are multiple units

involved with additional supports.

Example:

- French Army Spain Supports Marseilles to Gascony

- French Army Marseilles to Gascony

- German Army Brest Supports Gascony

- German Army Gascony Supports Army Burgundy to Marseilles

- German Army Burgundy to Marseilles

In this situation the French are dislodged in Marseilles.

Self bounces: People are used to the idea of ordering to keep someone out such as Army Spain--Marseilles and Army Burgundy–Marseilles.

But there is also the use to cut supports such as Vienna and Rumania

both going to Galicia to make sure that the unit there does not

support. However, people often don’t look at the possibility of

opponents using a supported attack on one of its own pieces to cause a

bounce.

Example:

Army Paris-Burgundy, Army Marseilles support Army Paris-Burgundy Army Burgundy supports Munich.

Since you cannot cut your own Support, such a combination allows you

to put a force of two on Burgundy to keep out an unexpected move by

another player on you.

Reading the Positions

It can be said the

learning curve on tactics in Diplomacy is very steep and short. It is

not a very complicated tactical game and the possibilities are limited.

When it comes to talking to and relating to people, this is a skill

that often you either have or you don’t and the changes in skill growth

are either non-existent or are by sudden massive jumps almost on the

level of an epiphany. Reading a position, or the fundamentals of

strategy, is one of the more elusive skills players need to learn and

it is a slow curve as it encompasses keen perceptions and a sense of

timing that often does not come without experience.

Reading a position is not about looking at the players or the

pieces, but at the relationship between the countries and the sum of

their pieces. From an initial position in Spring '01 you might

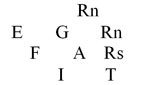

represent the positions of the countries like this: (Rn = Russia north and Rs = Russia South

When reading a position, ask yourself :

- Which countries are mostly a Front Line Country?

- Which countries are a backfield support country?

For example, one of the classic problems of the popular Western

Triple Alliance (England-France-Germany) is that England has a very

narrow front line position often composed of an Army in St. Petersburg.

Meanwhile Germany is committed all along its border with Russia and

Austria while France is mostly committed in the south. The result is

that England has a support role that translates out as having 4 or so

units behind both France and Germany. These units have nothing to do

except look for opportunities to pounce on someone. This is one reason

that when I advise England in a Triple that I want to keep going, the

English should wave builds so as to reduce the temptations.

The same is true when looking at the other side of the board that

faces a Western Triple: Italy, Austria and Russia become front line

positions with Turkey sitting back there in the corner with no where to

go.

As the turns go on, and countries expand in certain areas and

collapse in others, the relationship changes between a Front Line and a

Support power. Whenever you are fighting as an ally against a smaller

target always ask your self, “What happens next?”

Players often make a horrible strategic choice and, in effect, draw

a target around themselves for the next period. Take for example the

Western Triple. If Germany insists on going for Moscow and holding a

position in Sweden then where is England going to go when Russia is

dead? Even if England has just Moscow it’s an awfully small front to

project power to the south but not a bad one to go west from.

When you are trying to choose an ally in the middle game period, look to see who will be left when you are successful.

Does the position, REGARDLESS of the personalities, make sense in terms

of stability? Are you playing into a stalemate position or will there

be a further imbalance after the target is removed?

Where does your country stand as regards to being a Front Line power?

What choices will the other powers have next… or are you playing to a

situation where you will be forcing the other powers to ally against

you?

Think of the board as an enclosed box filled with seven water

balloons at the start, each rubbing against the other in different

degrees. As one is removed its space is taken by the expansion of the

other balloons. Who do the expanded balloons rub up against and what is

their frontage? What is the number of units that will be left

uncommitted?

Understanding the positions will give you a handle on what you should be talking about and worrying about.

Reading the Players

This is not about

unveiling a cold and calculated lie because an opponent scratches their

nose, or are duplicitous because they don’t look you in the eye. Since

many of you are going to play by email anyway, that would not be so

helpful even if such gestures and expressions were a reliable measure

of an opponent’s ethics. This is not about judging by the quality of

the person’s prose or use of grammar as an insight into their soul. Let

us be rational here and remember many players on the Net may have

English as a second language and then there are those like yours truly

who are still struggling with it as a first.

Reading a player is about understanding what they want, what they

think they want, what they are able to see and what you believe that

they understand about all of that. Once you are secure in your grasp of

the player, you can start to construct and sell a picture of the game

that weaves in its fabric what you want to accomplish and what they

want or are able to see. Here are simple steps to build up a read on a

player:

Goals

What is their goal in the game? When

asked, does the player say, “To win, of course!” or is he focused on,

say, the results of an entire tournament, not the immediate game? If

this is a social game, and a one-shot, then it’s very important to

understand what he considers achievement. So sometimes rather than

asking about his goal, ask about what he did in other games. If the

player comes back with answer such as, “It was a four way draw that I

just managed to get into,” then you know the player is looking at the

game from a draw-based position and not from a center count basis.

Communication Style

Does the player initiate

communication or keep to himself? Low key players that scream out

“victim” usually wind up as, guess what? The victim! In

discussions/communication is there player evidence of a plan in motion

or is he strictly reacting to others? Reactionary players tend to

overlook strategic positions of countries and can be manipulated into

situations where their choices become no choice at all and thus totally

predictable.

Climbing the Ladder

Does a player look at the

game as attacking ‘John’ or ‘Joey’ or is he detached and talks about

the countries? If you have a high profile in the Diplomacy

hobby then how do they react to other player’s reputations or prestige?

Are they more inclined to be a gunslinger going after the higher rated

or known player just because they have a reputation?

Where are they coming from? What is the player’s

background? The social aspect of hobby gaming is important not only for

the growth of your self as a human being relating to others, but also

provides a lot of clues as to the personality and response of the

person. Are they guarded and cautious by nature? Do they combine some

risk taking in their daily lives?

Do they come from a gaming background in war games or role players

or board game mini-max type play? Bridge Players and sci-fi fans made

up some of the first two groups that established the Diplomacy hobby

and it was with the arrival of the Wargamers a few years later that the

three provided the perfect combination of supporters to grow and

sustain the hobby. Each of these gaming backgrounds filled out nicely:

the Strategist, Diplomats and Tacticians.

The games we play often tell much of the way we approach the game of Diplomacy before emersion into the great game itself winds its way into the player’s soul.

So the basics where you start to learn are:

Read the Pieces

Read the Position

Read the Players.

Related Links

Diplomacy: Getting Started

Diplomacy Product Information

Edi Birsan is considered the first Diplomacy world champion

for his win in 1971BC, the first championship invitational game. He has

won numerous championship games since then in North America and

worldwide and is universally considered one of the game's top players.

More importantly, he has striven tirelessly for over three decades to

promote Diplomacy play in all its forms, at all levels, all around the world.