In Part 1, we examined the art of negotiation. Where negotiation is

a means of convincing other players to act as you desire, the art of

strategy is choosing the combinations of countries and overall

direction of movements (thrust east instead of west, by land instead of

by sea) which, if executed as planned, will result in a win. It is the

most neglected of the three aspects of Diplomacy play, the one

in which the average player is most likely deficient, and the one which

separates most experts from merely good players. The average player is

content to let his negotiations determine his strategy rather than vice

versa. Consequently he seldom looks beyond the next game year or the

immediate identification of enemy and ally to decide what he ought to

do later in the game.

I assume in the following that the player’s objective is to win, or

failing that, to draw. Those who eschew draws in favor of survival as

someone else wins will approach some points of strategy differently,

but until late in the game there is virtually no difference between the

two approaches.

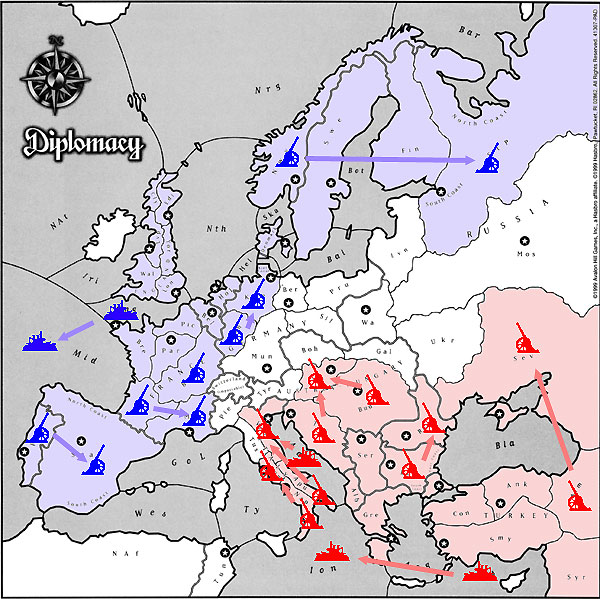

Fundamentals of Strategy

Strategy in Diplomacy is strongly influenced by the shape of

the board. Spaces near the edge are larger than central spaces, so that

movement around the perimeter is as fast as movement through the

middle. More important, the board is divided into two strategic areas

or spheres. The eastern sphere includes Austria, Russia, and Turkey,

while the western is England, France, and Germany. Italy sits astride

one of three avenues between the two spheres. The northern route

through Scandinavia and the Barents Sea enables Russia to have some

influence in the western sphere. The central route, between Germany on

one side and Austria and Russia on the other, looks short but is rarely

used early in the game.

Normally the game revolves around efforts to dominate the two

spheres. Early in the game a country rarely moves out of its own sphere

-- it can’t afford the diversion of effort until the conflict in its

own sphere is resolved. The country or alliance that gains control of

its own sphere first, however, becomes the first power that can invade

the other sphere and usually gains the upper hand in the game as a

whole. A continuous tension exists between the need to completely

control one’s own sphere and the need to beat the other sphere to the

punch. Commonly, two countries in a sphere will attack the third,

attempting at the same time to arrange a long, indecisive war in the

other sphere so that it will be easy to invade later. Sometimes the two

countries will fight for supremacy before the winner goes on to the

other sphere; more often, the players of the other sphere, becoming

aware of the threat from the other side of the board, will intervene

and perhaps patch up their own differences.

Poor Italy is trapped in the middle. Naturally an alliance that

endeavors to dominate a sphere wants Italy to move toward the other

sphere, probably to establish a two vs. two stalemate. The odd man out

in a sphere turns first to Italy to redress the balance of power. In

either case Italy is stuck in a long war. An Italian win is usually a

long game.

This discussion shows us the most important principle of strategy: everything that happens anywhere on the board affects every country.

If you concern yourself only with two or three neighboring powers,

you’ll never become an expert player (though glib negotiation skill can

go far to compensate for strategic deficiency). If you as Turkey can

influence the move of one French or English unit, it could mean the

difference between a win and a draw game years hence. If you can

strongly affect the entire country’s movements, even at that distance,

you should go far along the road to victory. The expert strategic

player knows where many foreign units will be ordered each season, and

he tries to gain that information subtly by using misdirection and

intermediaries; it doesn’t do to attract too much attention.

One of the most important considerations of strategy is the

attainment of a “stalemate line” by your country or alliance. Your

long-range goal is to win, but unless you are a romantic player who

prefers instability, your immediate objective is to be sure you can’t

lose. Once that's assured you can worry about going on to win. A

stalemate line is a position that cannot possibly be breached or pushed

back by the enemy. The area within or protected by the line includes

supply centers sufficient to support all the units needed to form the

line. There are many stalemate lines, and they have been discussed at

length in books and fanzines about Diplomacy. I will describe

the two major lines, which roughly coincide with the two spheres (and

not by accident!). You can find variations and other lines by studying

the board. (U = unit, that is, either army or fleet.)

Eastern Line: A Vienna, A Budapest S Vienna, A Trieste S Vienna, U

Venice, U Rome, U Naples S Rome, F Adriatic S Venice, U Apulia S

Venice, F Ionian, F Eastern Med. S Ionian, U Sevastopol, U Rumania. U

Bulgaria S Rumania, U Armenia S Sevastopol.

Western Line: U St. Petersburg, U Norway S St. Petersburg, U Kiel, A

Ruhr S U Kiel, A Burgundy, U Marseilles, A Gascony S Marseilles, U

Spain, U Portugal S Spain, F Mid-Atlantic, F English S Mid-Atlantic.

(Note that this line is solid only if the enemy has no fleets in the

Baltic Sea or Gulf of Bothnia and none are built in Berlin. This line

can be expanded to hold Berlin and Munich. An alternative is to place

nothing in Spain and Marseilles, F Portugal S Mid-Atlantic, A Brest S

Gascony, A Paris S Burgundy.)

With 13 to 15 centers, or as many as 17, within a line, a player is

almost certain of a draw. If he reaches the line soon enough and alone,

he can move on to prevent any other player from conquering the rest of

the board so that a draw or win is assured.

A drawback of reaching a stalemate line is that it can put other

players on their guard against you. If they know they can’t knock you

down to size, they’ll be reluctant to fight one another. This is a

danger any strong country faces, however, and it must be noted that a

perfectly played Diplomacy game should end in a draw, not a

win. (This depends partly on the players’ styles, of course -- a game

among seven extreme “placers" as discussed in part 1 will never be a

draw.)

You can win, then, only in an imperfect game, which means other

players make mistakes. The better the players, the more likely a draw

will be.

So much for the fundamental, strategic structure of the game.

Devising Strategy

When you devise a strategy, you plan the general direction of your

movement, expected allies, expected enemies, and what you want

countries not adjacent to yours to do. At each step you should have

alternatives -- barring great good luck, things will go wrong. The

styles and personalities of the players can strongly affect the

strategy you choose, but for this example, let’s assume that one player

is as suitable (or unsuitable) to your purposes as another.

First, consider the nature of your country. Is it a natural land

power, a sea power, or both? Is it on an outer edge of a sphere, an

inner edge (Germany or Austria), or in between (Italy)? Think about

this, look at the board, and decide where you’re going to get 18 supply

centers to win the game. You must take several centers in one sphere,

or in Italy, even if you control the other sphere entirely. Your plan

must include 1) a means of gaining control of your sphere without

hostile incursion from outside it, 2) attainment of a stalemate line in

at least one part of the board, and 3) penetration into the other

sphere (or Italy) to reach 18 centers. Note that Italy is within the

eastern stalemate line, and that the western line is anchored in the

eastern sphere at St. Petersburg. These seemingly minor points may have

a strong effect on your plans.

You can plan to jointly control your sphere with an ally, but then

the penetration must amount to eventual control of the other sphere as

well. You must include a means of reacting to any attempt to disrupt

your plan from outside your sphere. You must provide for other

contingencies; for example, if someone dominates the other sphere

before you dominate yours, you must be prepared to stop him. You must

be flexible while trying to implement your original plan.

Under this approach, Italy is out in the cold. Italy must either be

sure that neither sphere is dominated by any country or alliance early

in the game, allowing Italy time to grow, or it must quickly dominate

one sphere. From the strategic point of view, Italy is definitely the

hardest country to play.

Here is a brief example of a strategic plan for England. Assume you

don’t like the Anglo-German alliance or the German player is

notoriously unreliable, so you plan to offer a limited duration

alliance to France for a joint attack on Germany. You’ll offer Belgium,

Munich, and Holland to France while you take Denmark, Kiel, and Berlin.

You don’t mind if Russia and Germany get into a fight over Sweden, but

you want Russia to concentrate, with Austria, on attacking Turkey. This

will leave Italy free to peck away, initially at Germany, later at

France. When your alliance with France expires you will attack France

with Italian help, and at the same time pick off Russia’s northern

centers (Germany should fall sooner than Turkey -- if necessary you’ll

give Turkey tactical advice). You want Austria to attack Russia after

Turkey falls. This is important, because Austria-Russia would be a

formidable alliance against you. It is possible but not likely that you

could reach a stalemate line as Italy collapsed under an attack from

Austria, but it is much better to have most of the eastern units

fighting one another. In the end you should be grinding down an

outnumbered Italy (England will gain more from attacks on Germany and

France than Italy will, by nature of the positions) while Austria keeps

Russia busy. For supply centers you want England, France, Germany, the

Low Countries, Scandinavia, Iberia -- a total of 16 -- plus any two

from St. Petersburg, Warsaw, Moscow, Tunis, and Italy.

To go into all the alternatives where this plan might lead would

require pages. As one example, the alliance with France could be

extended if France appears about to be drawn into a protracted war with

Italy. That time could instead be used to march into Russia and the

Balkans.

Differences Between Countries

Now we come to individual countries. Reams of statistics are

available about the success of each country in postal play, but the

percentages have varied over the years, and statistics of American and

British postal games show some differences.

Generally, each country has a good chance of success except for

Italy, which is handicapped by its between-the-spheres position.

(Pirated South American versions of Diplomacy give Italy a

fleet instead of an army in Rome and add a supply center in North

Africa. These changes strengthen Italy and probably make Diplomacy a better-balanced game.)

Russia tends to be an all-or-nothing country because of its extra

unit, its long borders, and its connection with the western sphere and

stalemate line. Russia wins outright more than any other country. The

inner countries, Germany, Austria, and Italy, are harder to play well.

The next seven sections briefly state what to look for when you play

each country. "Natural neutrals" are neutral supply centers which are

usually captured by the same Great Power during 1901. The most common

opening move is also mentioned, but remember that tactics are

subordinate to strategy. Even the most common openings are used less

than half the time.

One other point remains to be made. Western countries can wait

longer than eastern countries before committing themselves to

agreements. The easterners are too close, with too many centers at

stake, to wait.

Austria

Land power, natural neutrals Serbia and Greece.

Turkey and Austria are almost always enemies because Austria is at a

great disadvantage when the two ally. Turkey usually owns territories

on three sides (Mediterranean, Balkans, Russia) if the alliance is

successful, and Austria is just too easy to stab. Russia and Italy are

the best alliance prospects, especially the former. If Russia and

Turkey ally, Italy can often be persuaded to aid Austria in order to

avoid becoming the next victim of the eastern juggernaut. Germany

virtually always agrees to a non-aggression pact, nor should Austria

waste units in the western sphere. The early game is often a desperate

struggle for survival, but a good player can hang on until events

elsewhere and his own diplomacy improve his position. Unfortunately,

normally Austria must eliminate Italy to win because the seas and

crowded German plains halt expansion northward; this land power must

become a sea power in order to grab the last few centers needed.

Commonly Austria opens with F Trieste-Albania and A Budapest-Serbia,

followed in Fall by Serbia S Albania-Greece. A Vienna is used to block

whichever neighbor, Russia or Italy, seems hostile, by Vienna-Galicia

or Vienna-Trieste or Tyrolia.

England

Sea power, natural neutral Norway.

England has an excellent defensive position but poor expansion

prospects. An Anglo-German alliance is not as hard to maintain as the

AustroTurkish, but neither is it easy. England must go south when

allied with Germany, but it can hardly avoid a presence in the north,

facing Russia, which puts it all around the German rear. England-France

is a fine alliance but it may favor France in the long run. Whichever

is the ally, England may be able to acquire Belgium by working at it.

Patience is a necessity, however, unless Italy or Russia comes into the

western sphere. If either does, to attack France or Germany, England

must gain centers rapidly or be squeezed to death between its former

ally and the interloper.

England can win by sweeping through Germany and Russia, but all too

often the eastern stalemate line stops this advance short of victory.

Similarly, a southern Mediterranean drive can founder in Italy, but

this part of the defenders’ stalemate line is harder to establish. If

England can get up to six or seven centers, it has many alternatives to

consider.

Usually England opens with F London-North, F Edinburgh-Norwegian, A

Liverpool-Edinburgh. The army can be convoyed by either fleet while the

other can intervene on the continent.

France

Balanced land and sea power, natural neutrals Spain and Portugal.

France may be the least restricted of all the countries, vying with

Russia for that distinction. There are many options for good defensive

and offensive play. Alliance with Germany or England is equally

possible, but it is easier to cooperate with England. An astute French

player can usually obtain Belgium regardless of which country he allies

with. Italy’s movements are important to France because penetration

into the Mediterranean is usually necessary late in the game, if not

sooner. Russia can be helpful against England or Germany. Even a

French-Russian-Italian alliance is possible against the Anglo-Germans.

At any rate, if France is attacked, there are several players to ask

for help.

A common French opening is F Brest-Mid Atlantic (heading for Iberia), A Paris-Burgundy, A Marseilles-Spain.

Germany

Land power, natural neutrals Holland, Denmark

Like Austria, Germany must scramble early in the game, but its

defensive position is better, alliance options are broader, and Italy

isn’t quite clawing at the back door.

Alliance with England is difficult because England usually commands

the German rear as the game goes on. (As England I have been stabbed --

ineffectively -- several times by Germans who couldn’t stand the

strain, though I had no plans to attack them.) Germany-France is a

better alliance, though France may gain more from it, and Germany can

be left dangerously extended between France and Russia. Either romantic

methods or great patience is required. Fortunately, Austria rarely

interferes early in the game (nor should Germany waste effort in the

eastern sphere) and conflicts with Russia are rare if Germany concedes

Sweden.

A common opening is F Kiel-Denmark, A Munich-Ruhr, A Berlin-Kiel. Kiel-Holland or Munich-Burgundy is also common.

Italy

Balanced land and sea power, natural neutral Tunis.

Italy needs more patience and luck to win than anyone else. Italy's

defensive position is actually good, but immediate expansion

possibilities are very poor. Don’t be hypnotized by all those Austrian

centers so near. If Russia and Turkey ally, Italy’s lifespan isn’t much

longer than Austria’s and full support of Austria is required. Italy

tends to become involved in the eastern sphere more than the western.

Unless England and Germany are attacking France, Italy stands to gain

little in that direction. Although Turkey seems far away, Italy can

attack her using the “Lepanto Opening” in Spring 1901 -- A Venice H, A

Rome-Apulia, F Naples-Ionian (this is the most common Italian opening),

followed in Fall by A Apulia-Tunis, F Ionian C Apulia-Tunis, build F

Naples. In Spring 1902, F Ionian-Eastern Med. (or Aegean), F

Naples-Ionian, followed in Fall by convoying the army in Tunis to

Syria. This attack requires Austrian cooperation, of course.

Russia

Balanced land and sea power, natural neutrals Sweden, Rumania.

With a foot in the western sphere owing to its long border, Russia

has an advantage in expansion. Its defensive position, however, is

weak, despite the extra unit. Russia often feels like two separate

countries, north and south, and it may prosper in one area while

failing in the other. The eastern sphere is more important and usually

gets three of Russia’s starting four units.

Russia has no obvious enemy. Because the Austro-Turkish alliance is

so rare, Russia can often choose its ally -- but mustn't become

complacent! In the north, Germany can usually be persuaded not to

interfere with Sweden. An Anglo-German attack will certainly take

Sweden and threaten St. Petersburg, but Russia can lose its northern

center and still remain a major power. A Franco-Russian alliance can be

very successful provided Germany and England start the game fighting

one another.

A common Russian opening is F St. Petersburg (sc)-Bothnia, F

Sevastopol-Black, A Warsaw-Ukraine, A Moscow-Sevastopol. The move

Moscow-St. Petersburg is rarely seen (and very anti-English).

Warsaw-Galicia is anti-Austrian (with Moscow-Ukraine).

Sevastopol-Rumania is very trusting of Turkey.

Turkey

Balanced land and sea power, natural neutral Bulgaria.

Turkey has the best defensive position on the board. Its immediate

expansion prospects are not bad, and at one time it was notorious in

postal circles for spreading like wildfire once it reached six or seven

units. Now players realize that an Austro-Russian alliance, or the

Italian Lepanto opening, can keep Turkey under control.

Austria is an unlikely ally -- see Austrian notes for why.

Russia-Turkey can be an excellent alliance, but if Russia does well in

the north Turkey will find itself slipping behind. Nonetheless, beggars

can’t be choosers. The Italo-Turkish alliance is seldom seen, perhaps

because Italy too often becomes the next victim for Russia and Turkey.

A fight between Italy and Turkey on one side and Russia and Austria on

the other is rare, because Italy prefers to go west and hope Austria

will attack Russia after finishing with Turkey. Turkey has plenty of

time to look for help from the other side of the board while fighting a

dour defensive, but help usually comes too late.

A common Turkish opening is A Constantinople-Bulgaria, A

Smyrna-Constantinople (or Armenia, to attack Russia), F Ankara-Black.

The favored alternative if Russia is definitely friendly is

Ankara-Constantinople, Smyrna H.

In Part 3, we’ll turn to an examination of tactics in Diplomacy.